On the shoudlers of giants

Factors for planning a hike are numerous and daunting: Shuttles, business hours, resupply packages, and the entire minutia associated with those is enough to make the planning part of the brain short circuit and freeze.

Then there’s the unknown: What if I have to reset a femoral fracture? What if someone gets altitude sickness? What if I get bitten by a snake? What if I get attacked by a bear? What if I get attacked by a bear that was contemporaneously bit by a snake? What if that snake had hypothermia? What if I get seriously hurt and no one knows where I am? What if someone kills me out here? What if I just wake up dead one day?

It’s never as bad as all of that, I assure you, but the fear of the unknown is very real. I was fortunate in that Lindsey was the planner, and she was a damn good one; the perfect mix of bookworm, researcher, and logistician. My approach was a much more audacious one, a tinge less methodical and consisting only of the following mentality: “You won’t die out here. Let’s go.”

I’ve come to rely on my problem solving skills, resourcefulness, and general outdoor skills to get me where I need to go. I think that setting a training plan, meal testing, and accruing lighter gear are all excuses to delay doing the hike. I dare say that I prefer when things don’t go to plan. That’s where adventure lives- in those strange crevices of unforeseen unpreparedness and ever changing conditions. As a hiking team we struck a complementary balance. She was 60% planner, 40% outdoor woman. I was 99% outdoor guy, 1% linguist that knew the definition of “plan.”

Over the course of the prior days, our plan had faltered. In the beginning, when we were young, we were going to hike the John Muir Trail, drink whiskey on Whitney, hike down to the trailhead, hitchhike to Lone Pine, shuttle back up to Yosemite. Some photos, some high fives, a cool story to tell, and then back to Texas.

The trail teaches you a lot of things. One of the first and most eye opening and valuable things I learned- You can get anywhere by putting one leg in front of the other and repeating. Over creeks, snowfields, mountains, roads…you’ll get there. No training regiment, guidebook, map, class, assurance, or safety net needed. Find the path in the dirt. Walk. Keep moving forward. Stay vertical. You’ll get there.

Beyond Glen Pass

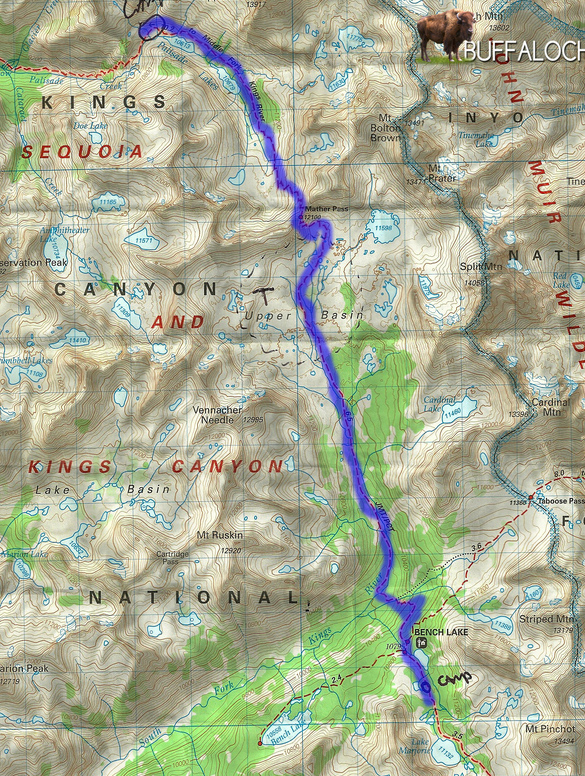

Standing on Glen Pass, it was never more apparent that not only had our original plan faltered, but it had stalled, started a nose dive, and then caught ablaze. Our plan now was to eject, and there’s a whole lot less certainty that comes with that. Specifically- getting back to civilization once we reached the end of the trail. In truth, there really isn’t much you can do. We knew we were exiting. We’d deal with getting back to actual civilization when we hit asphalt in Onion Valley, similar to what we did when we started down that long asphalt stretch of road from Red’s Meadow to Mammoth…we’d walk until we got to Independence, some 13 miles down a winding mountain road. One foot in front of the next. In the worst case scenario, we could camp at the campground there before arranging transportation or hitching a ride. We’d figure it out…

After Lindsey emerged from behind the particularly beefy rock she’d chosen to hide behind, we didn’t tarry on the serrated ridge. Though we had no company on the pass and no one in sight on the trail in either direction, we knew we had miles to go and another mountain to climb before the day’s light was done so in short order we were steaming downhill on steep switchbacks.

My water bottle was about empty after the massive effort spent going over Glen Pass.

“I’m thirsty…” I whined.

Sometimes I thought that if I was an annoying, petulant child that it would make the miles go faster. Not that they needed to go faster, it was more of a way to entertain myself. Unfortunately, my audience didn’t like my act much and grew instantly tired of this bit every time I did it. This was often. It was a bit I adapted from Russel, from the movie UP. I paraphrased the movie lines and would typically spew forth the following in a whiney childlike voice, no fewer than 3 times per day-

“I’m tiiiiiired. My feeeeet hurt. I need to go to the baaaaathroom. Can we stop walking?”

It amused me every time. Lindsey groaned a few steps ahead of me and muttered something under her breath. Something good, undoubtedly. I smiled a satisfied smirk and remembered my water bottle that was in my hand.

“Oh yeah…almost empty…”

My smirk turned to a slightly perturbed grimace.

The trail was more sheltered from the wind on the southerly side, almost to the point of an eerie calmness. The rocks had morphed from black on top of the pass to grey to a tan color with the faintest amount of orange tint to them. The lot of rocks sat silent and baked in the warm sun. It was a dry and dusty descent in an otherworldly landscape of hard angular shards. Scree slopes and fallen boulders and the remnants of once proud spires lay beneath our feet with no sign of vegetation around. I like to imagine that we kicked up a fair amount of dust in our very deliberate descent. After 30 or 45 minutes, Charlotte Lake could be seen shimmering in the distance.

The stretch from the final Rae Lake to Charlotte Lake is long, and it’s quite dry. We were both low on water so it was a relief seeing the source of our impending hydration. 1st Rae Lake was the last reliable filling point, and the ascent over Glen and the xeric extraterrestrial rockscape on the other side offered only opportunities to suck down sips of water from an ephemeral spring here and there but never a spot to refill.

Descending Glen Pass

We walked the rocky wasteland further and as we descended it became dotted with greenery. Stout grasses at first, then some short pines that offered a respite from the strengthening afternoon sun. Soon the trees had gathered in density and height enough to pass for a sparse forest. A sparkling gem of ultramarine flashed through tall brown branches and long slender fingers of green pine needles.

“I’m thirtyyyy. I’m tiiiiiired….my feeeeeet hurt….”

Lindsey didn’t acknowledge me, but I thought the comedic timing was perfect.

One of the best parts about hiking is trail signs. Trail signs mean you’re getting somewhere. It means you have a choice (most times) or that you need to take in some important new information, like how there are no fires permitted, or how there are bears around that will take your foodstuffs. At the bottom of the steep, seemingly incessant descent we came to such a sign. It was your standard directional sign- an arrow pointing to Charlotte Lake, and arrow pointing down the John Muir Trail. I liked the sign so much I leaned on it while Lindsey went down a short spur trail to extract water from Charlotte Lake.

No sense in us both walking further than we had to…

There are two trails that exit over Kearsarge Pass. One is a high road, the junction for which meets up with the John Muir Trail about .3 miles before the turn off for Charlotte Lake. The high road doesn’t go by any water sources, though. The lower road takes you down in elevation but scampers past the junction to Charlotte Lake and the northern side of Bull Frog Lake before ultimately climbing back up the 300 or so feet lost as it meets the high road. Both paths converge after a couple of miles and turn in to a singular trail that leads over Kearsarge Pass and down to Onion Valley.

On a dusty, warm, barren clearing on a small hill we reached our junction with the low road. The sign stared at us like a bouncer. Kearsarge Pass via Bullfrog Lake, this way. John Muir Trail, the other way.

I knew if I stared and thought about the sign and the implications of our turn long enough I might over think things or continue down the JMT. I glanced at the sign, looked down the trail towards Kearsarge Pass and Onion Valley, and put one foot in front of the other. That was it. We were done with the John Muir Trail.

Some 5 or 6 weeks prior to that exact moment, a man that called himself Riley appeared at the end of the Onion Valley Road just west of Independence, California. It might not be ironic, but it is fitting, if nothing else, that this man would be the first person we’d have met in Tuolumne Meadows. Riley was camped adjacent to us in Tuolumne Meadows as he had just finished his trek from Kearsarge to Tuolumne; the exact opposite of our eventual path.

The first night of the entire trip, with the glow of the fire in the center of our world, and the world rife with excitement, wonder, and adventure, Lindsey and I listened to Riley talk of his failed attempts at getting a Whitney permit, of bear sightings, of sharing a single person tent with his girlfriend for a couple of nights when she joined him, and of the Rim Fire.

“Yeah I had to come in over Kearsarge.” He said.

I nodded and smiled, assuming he had mispronounced something since I’d never heard of anything called Kearsarge.

“Going South to North is hard, but by day 4 or 5 your body adapts and you’re good to go.” He’d said.

Riley was long gone by now, but I couldn’t help but think about him walking this same stretch of trail, only in reverse. We marched out knowing it was an end. Riley pounded the dirt with his trail runners knowing it was the beginning.

There’s uncertainty with beginnings. As the sun rises, no one knows what the day might bring. Just so on a hike of this scale. There’s expectation, a buildup, and finally a resolution; a sunset. For Lindsey and I, we could see the sun was setting sooner than we’d originally planned.

Kearsarge Pinnacles

We could see the sun setting literally as it set the mountains around us aglow in a warm light. Trail and trees and rocks and small rodents and mammals and dirt and switchbacks came and went as we advanced further down the trail and higher up the side of an exposed slope towards Kearsarge Pass. A magnificent ridge mirrored the other side of the valley we were climbing out of. The Kearsarge Pinnacles. Stark and sharp and steep. I stopped in the middle of the trail to admire them across from us and to catch my breath.

“I’m. Tired. My. Feet…”

I trailed off and drank some water.

It looked as though the pass was within sight, but I’d been burned too many times before to think for a single second that the end of a mountain climb could ever be in sight. It’s an attitude which makes for really anti-climactic summits because I’ve spent the whole climb conditioning myself to believe that whatever clearing or apex it is that I see…it CAN’T be the summit. I hate being disappointed.

The route to Kearsarge pass was similar to Glen Pass in that the final ascent was a long, drawn out gradient instead of a litany of short switchbacks. I like the long ascents more because after a while, it seems like you’re walking on a flat surface. You’re really climbing at about 10 to 20 degrees, but without the perspective added by switchbacks immediately above and below your position, it seems flat. The long gradient also affords a peak at your ultimate destination ahead, be that the pass or a false summit.

I sped up my pace as the gradient pointed dead ahead towards a distinct notch flanked by fractured, angular boulders on either side. The climbing…all of the daily, ceaseless climbing. This was it. All the steps, all the miles, all the contour lines on maps and vertical feet ascended: this was the final ascent. Everything else was literally all downhill. I started to get a sincere sense of overwhelming excitement. Every milestone and in a way, every step, was a final moment. Final water stop, final trail split, final pass, final climb, final step. I took a deep breath and relished in that moment as I approached the end of the uphill, exposed climb on the side of a mountain.

And then I saw the switchbacks above me.

“I warned you about that…” gloated the part of my brain that is smart enough to not walk down the cookie aisle at the grocery store.

“I thought for sure this time it would be different.” Replied the part of my brain that makes me eat a bag of oreos in one sitting.

4 switchbacks. The final 4 switchbacks followed by 400 feet of linear distance were all that stood between us and the high point of Kearsarge Pass. I walked in front of Lindsey, fueled by another microburst of adrenaline. As I stepped on to the ridge, I raised my walking stick above my head with one hand in triumph. On the pass I lingered, waiting for Lindsey.

That very point I stood held a lot of power. It was a spot that divided east from west, light from shadow, Fresno Country from Inyo County, National Park from National Forest, victory from defeat, the trail from home. Lindsey joined me not long after and we rested and took the requisite photos.

Beyond the pass: An absolutely gnarly traverse across a seemingly infinite slope of rock, a steep descent and a long, lush valley of pines and lakes and streams.

I stared in to the setting sun and gave a look back on the High Sierra, the unrestrained rays of light assaulting and bleaching the grey and white granite, casting shadows on where we were to be heading. The wind blew cool, clean and quietly over the countless peaks and spires and notches and serrations of the Sierra, hiding thousands of secret valleys and pristine lakes. Going over Kearsarge pass was like walking out the door of a strange, beautiful, enchanting, enrapturing landscape where your only job and your only responsibility is to exist; to be. As I stood there looking west on the shoulders of a giant, gazing at the place from whence we’d come, I saw further than I’d ever seen before.

The atmosphere that rests high atop the granite spires of the Sierra Nevada is clear, and not surprisingly, I found that clarity of mind comes with it as well. I saw the landscape as it was, but also salvation and life as it was meant to be lived. For a mere 18 days we lived the bulk of our lives sleeping inches above the dirt in a non-permanent structure, but it felt like a wonderful life time. Our days were filled only with hiking. Thinking. Talking. Arguing. There were no bills, no deadlines, no current events, no sports, no shootings, no new products. It was pure; simple. The mountains absorbed the foolishness of everyday life and the lunacy we force ourselves to deal with as we swallow the putrid pill of social acceptance that we determine we must take so as to fit in with the rest of the majority who have chosen that medication as well.

The mountains didn’t care that we were there. They neither shunned nor accepted us. And that humbling feeling of total insignificance was absolutely liberating. The mountains were not our world that we’d created, tamed, and bleached; The elements fought out here, and we were travelers through their battlefield. The clouds cried and when particularly enraged, they would spit pellets of ice. Trees lived, died, and lay on the ground to rot. The winds would whip and howl strong enough to move mountains and in the next breath, blow a gentle breeze across our brow. Streams would flow in to lakes which would feed torrents and roaring waterfalls, or lakes would dry up from a lack of snow melt and wither in the light of day. Under the golden orb of the sun and beneath an effervescent spectator of a color changing sky, the world put on its show and for a short time, we had a front row seat to see things as they were meant to be; to see the world as the world was before it became infected with waste and filth and trash and excess and garbage.

I turned away from the sun to look at my shadow in front of me, and I moved my right foot down the trail. The left foot passed it. We had been in a paradise.

A few steps and it was gone from sight, and we were gone from it.

In every sense, as I stepped on the other side of the crest and began past Kearsarge Pass, I was leaving heaven on earth. And that’s a very strange, very wrong sensation.

The Climb

Silence.

Silence.

Silence.

THUNK.

It sounded like someone threw a marble in to the lake.

I batted my eyelids and managed to hold them open for some moments as I thrashed and rolled violently a quarter turn like a bratwurst might do as it pops and convulses in its own grease.

I had become able to sense when Lindsey was around. It may have been because she exuded a lot of heat and gave her sleeping bag a lumpy texture and appearance. Lumpy in the best of ways; as if a svette hiking machine of a human were resting inside of the contorted down and nylon lumps. I knew immediately that she was not in the tent, and confirmed it by flopping my arm around blindly and recklessly where she should have been lumping. I stared off and contemplated.

“Eating, maybe…”

The sensible, simple side of my brain was first to the punch in this dialogue.

“Or eaten… and If she got eaten then that bear is coming for us, and we can finally execute the black bear attack protocol.” The nefarious and angry-to-be-awake counterpart of my mind offered.

“That’s stupid, and will get us killed.”

“OR it’ll get us on good morning America…”

“Your idiotic plan of drop kicking the bear and putting it in a sleeper hold while someone records the footage is entirely contingent upon someone recording it. There’s no one else here.”

“That’s a good point.”

So I settled back in for more sleep. Didn’t matter what time it was, it was too damn cold and too damn early. Besides, I was fairly sure I caught a glimpse of Lindsey wandering around out there. A few more spastic sausage-roll maneuvers in my mummy bag, a couple of blinks, and I prepared to enter back in to the amazing world of rest and recuperation in the great outdoors.

Silence.

THUNK.

THUNK THUNK.

Physics made the sun rise; noisy ass fish made me rise.

The sun served as a morning breakfast alarm and the lake came alive. The trout and cohabitating creatures of Dollar Lake feasted on morning swarms of bugs, dragonflies, and whatever small insects dared get too close to their hungry fishsy mouths. This ritualistic daily feeding of the fish was a cruel mockery. Our bear canisters were nearly empty and held only the remnants of the things which we wanted to consume the least. Some oatmeal. Peanut butter (which had surprisingly taken a long time to reach the point of overstaying its welcome, but it had by now) and some small fillets of mackerel in a vacuum bag because that seemed like a good idea at the time when we were shopping.

It was ironic in some ways because as the food chain goes, we could have eaten those fish in the lake. We were heading home because we were out of food. And here these fish were…eating because they were home, because they know how to survive, because they don’t store their food in a lexan container, because their fish societal structure doesn’t require that each fish talk to the Dollar Lake Fish government to obtain a license to eat bugs. In eyeshot and earshot, there swam a multitude of cold, delicious, white, fleshy, nutritious snacks…

I popped out of my sausage casing (if we’re still using that metaphor) and walked in to the cold mountain morning air to stare at the land under an eastern sun’s light. Finn dome towered on the skyline as dollar lake served to be a reflective backdrop of the green and gold and grey landscape. Behind it all was a bold, blindingly blue morning sky. The early light came on fierce and bright, but as ever, we were sheltered from the direct glow of the sun by rounded ridges and elderly pines. The morning was cold, maybe 30 degrees; colder than any of the other mornings that proceeded but this morning seemed especially clear, bright, and still. No one ever came to join us and camp at Dollar Lake, and we’d not seen anyone pass us on the trail yet. For the night and the better bit of a morning, we were the only ones in the world. It was us, our gear, and the symphony of splashing fish.

Not long after rising from the frosty tent, we’d gone through our own morning rituals, packed our gear and loaded up our backpacks which at this point were svelte. Moving meant warmth, and warmth was my only motivation for ever moving in the morning. If it were up to me (and even when it wasn’t up to me) I’d stay in the sleeping bag until 10am or 60 degrees, whichever came first.

Layering really is all that it’s cracked up to be, and we had become proficient at it on this trip. As I suited up in the morning I skipped the base layer pants because I knew I’d be taking them off in short order. I opted for my cut off shoes, Icebreaker merino wool socks, icebreaker 200 weight boxers, mountain hardwear canyon shorts, long sleeve REI prototype base layer, Columbia omni-freeze shirt, down sweater, and turtle fur beanie. Lindsey bundled up in layers that would make the Michelin Man look like a slut. Ready to endure what may come, we wandered southerly on the unbeaten portion of the trail.

Through the gently radiused valleys of gray rock and granite peaks that had been rounded by time, weight, and ice, the trail snaked towards Finn Dome winding its way between robust, thick, hard scratchy golden grasses, andcold, shady pine trees. The path paralleled a softly spoken creek that fed the life from Arrowhead lake in to Dollar Lake.

The day was going to be a battle, that was apparent from the time the buckles on the backpacks clicked and load lifter straps were pulled tight. It’d be a mental battle more than a battle against the elements or terrain though there was no mistaking the physical obstacles ahead: Two mountain passes of great renown and great height- Glen and Kearsarge. The miles between them couldn’t be construed, shortened, or shortcut. (I only know that because I stared long and hard at topo lines to find an off trail shortcut without any success…) These physical struggles of pumping lungs and pounding hearts and fatigued muscles are straightforward, and the outcome is almost always a certainty- we will make it. Whether it’s a frozen creek, a smoke filled valley, an afternoon thunderstorm above tree line, a multi-thousand foot climb to a mountain pass: We would make it. With time and food and movement, we’d make it. That is the simple eloquent beauty of living out of a backpack in the mountains. Given the time, and given the movement- You’ll make it anywhere you can see and many places you only imagine.

Internal battles, mental and emotional, aren’t so clear cut. A battle between triumph and failure had been simmering for days as the fuel for our physical battles which was stored in the bear canister evaporated. Could we stretch out what food we had left? Could we find some strangers who’d lend us their refuse food? Would ranger stations have snacks or rations? Can we hike faster? All of these things played out as potential moves on the chess board. All with the same end- checkmate. We knew the night before what our plan was. But as the night grew dark and light again, and even as we walked down this trail, it was hard to accept the reality. This was no longer a battle, it was a surrender. This day was in every way THE end. The end of the miles, mountains, dirt, dust, sweat and sun. The end of the high altitude air, cold wise rocks, gossiping creeks, playful clouds…the end of it all.

Sure, we missed home. God damn right I missed cheese burgers. And pizza. And refrigerated foodstuffs, and vegetables, and cold drinks, and ice cream, and hot water, and being clean, and soft beds, and internet, and the convenience of civilization, but I did not want it to be the end. Lindsey did not want it to be the end.

On the trail we marched at two miles an hour, wafting a gentle fragrance of ripe human in to the atmosphere in our wake. Two kids who saw a name on a brown sign during a ridiculous trip to Yosemite 6 years earlier. Two kids who’d never backpacked more than 1 consecutive night prior to this. The solemnity of the situation bounced around with the gravity of consequences in my head, and our boots shoes unwaveringly poured forth the steps that would make the miles that would lead us to the home that we were excited to see, but didn’t necessarily want to be at.

Rae Lakes is one of the areas of the JMT that seems to stick in your head more than others, possibly because it’s beautiful and oft talked about by hikers, schemers, and locals. Possibly because there’s a ranger station and a lot of hiker traffic there. Probably both of those things. It snuck up on me because I was mostly anticipating and mentally preparing for the climb up to Glen pass. From Dollar Lake to the summit of the trail on Glen pass is only slightly more than 3 miles ahead and 1800 feet above.

For those 3 miles, yellow rays of sunlight gradually oozed in to the darker grey spaces around the trail like honey and began to warm the ground. We passed a small creek that was covered in a fraction of an inch of the clearest ice I’d ever seen. Naturally we broke it with our feet. It yielded with a satisfying crack after a little pressure, its presence alone a testament to the night time temperatures in this basin.

Ahead on the trail- an idyllic setting of clear, cobalt blue water, dirt, trees, and relentless granite rocks.

On a glowing granite mound by the waters of the northern most Rae Lake, we stopped to adjust our layers and make breakfast. Those hikers who hadn’t hit the trail by now were just starting to rouse from their camps near the lake basin. I fired up a hexamine fuel tablet to boil some UV purified high sierra water inside a titanium cup while Lindsey grabbed our last 2 prepackaged custom made oatmeal baggies. Lindsey created a lot of the food back in Texas. The freezer bag creations were delicious. This particular one was your standard oatmeal goodness with added craisins and powdered milk and some nuts. Our last breakfast meal that we had. I set out the goal zero solar panel to steal some of the sun’s energy for my battery pack and took the opportunity to lay on a rock and absorb as much of the warmth and light as I could while we cooked, ate, and reshuffled clothing.

We stayed there longer than we should have, but most of our stops had this same ambling ambiance.

Blanketed now entirely in light, warmth, and fueled by the recent nutrients, the hiking began in earnest. Mountains awaited, the only way forward on the trail was climbing over them. With a final cinch of straps and a matter-of-fact exhale as if to finally resign ourselves to our impending fate, we took a step down the path.

They’re just numbers, these elevations. But they can be daunting numbers. Your body becomes better conditioned and you get faster as you become accustomed to the altitude and weight and regiment of walking all day, but nothing ever gets easier. The endorphins and the happiness far outweigh any pain and struggle, true.

I tend to make a bigger deal of the elevations in my head than any normal person, which affected how much I could just sit and enjoy the moment by Rae Lake(s).

Back on our first round-the-west trip, we stopped at the North Rim of the Grand Canyon and hiked down to Roaring Springs. Easiest half of a hike I’ve ever done. We practically skipped down the soft dusty trail, whistling a tune as we sped past massive mounds of mule shit. The red dirt on the trail, the canyon walls, the steaming piles of wretched urea smelling excrement all flew by. It was a hot, dusty, clear day. I was a 300+ pound mass of man bounding down a well graded slope with precision at speeds previously thought to be impossible for a man of my girth. So I thought.

As we tore ass down the trail, a man with one leg passed us…

This is what exhaustion and defeat in the Grand Canyon looks like.

After about 4.5 miles of our high speed sauntering we reached Roaring Spring. I was never one to plan things out. Lindsey would pick a place or a hike that sounded good based on her readings in a paper or guidebook, and I’d oblige. I’d know the name of the trail, what it is we were going to see, and I built a world in my head of what I thought it should look like. This waterfall/spring was a total let down. What I had imagined as Havasu Falls was an uncorked flow coming out from a cliff that looked like we couldn’t even get close. Disappointment set in, not too dissimilar from the feeling that fogged me over after learning I would not be getting my hamburger at Red’s Meadow. After snacking and resting at a hot sandy picnic table at damn near the bottom of hell’s drainage ditch, the inevitable ascent back to the top of the canyon loomed large.

Seeing no use of prolonging the inevitable, we reversed our direction and headed back up the trail. I still remember those first handful of steps ascending back up the trail. Hiking in to a canyon is the exact opposite of climbing a mountain as it turns out.

“You practically sprinted down this canyon, so all you need do is power walk up it. You can do that. You’re an athlete.” Said the part of my brain that thinks all homeless people write the honest truth on their cardboard signs.

“It’s a long hike. Go slow…You have all…”

“Shit, we’re out of breath. Let’s take a break.”

The climb out of the canyon was slow. So slow. I’d walk some steps and then rest a good minute. Lindsey did fine. She was hot and tired, but I was the limiting factor of speed. We stopped along some huge cliffs for a rest as they afforded some respite from the brutal sun.

I’ll be damned if that old one legged man didn’t come hauling his happy half an ass up the trail leaving a cloud of mule feces tainted dust suspended in the thick, hot, dry air behind him. I was appalled. He was moving at thespeed I envisioned myself moving. Assaulting the gradient, leaving his tell-tale track of one audacious boot print and 2 lateral crutch dimples in the sand.

“But…but that man. He only was one leg.” Pondered the part of my brain that doesn’t understand how reeces peanut butter cups are made.

“You’re fat and slow. Why are you shocked?” replied the part of my brain that’s not responsible for my hunger.

For hours we walked up and up and up. Lindsey’s cheeks turned a bright red from sunburn and heat and dehydration. I can feel my heart in my ear drums and my pride had gone somewhere inside of me where broken things are stored. We reached the car as shadows were long. It was still light, but a quickly fleeting illumination that said we were slow…slower than 1 mph slow. I was all too happy to jump in the Tacoma and head down the road. I had driven not even one mile down the road back to Jacob’s Lake where we were staying. I remember distinctly that my mouth was silent, but the internal dialogue was omnipresent.

“Don’t do it…don’t you dare do it.” Said the prefrontal cortex.

“blah.” Replied the hippocampus.

“Do not…”

“Tell the human to pull the car over.”

I don’t remember if I rolled down the window or walked around to the passenger side, but what spewed forth from my innards was an awesome fountain display that an uncultured homeless man might mistake for the Bellagio. I’ve never thrown up so hard or so much in my life. All of the water I drank over the course of the day. The hand full of trail mix…all of the snacks and drinks and nourishment. None of it went in to my body in those hours of hiking out. It all just sat inside my stomach for some reason. And after I’d pulled my sorry ass out of the canyon (no thanks to the energy and electrolytes that I tried to provide) my body decided to get rid of all of that.

I felt great afterwards. My heart rate didn’t come down until a day or two later in Bryce Canyon. In retrospect, that may have been due to a severe state of compensated volume shock. That Grand Canyon hike has given me PTSD when it comes to hiking canyons. And that is why I tend to find altitude a significant psychological factor.

But on a Thursday in late September, the granite wonderland of the Sierra Nevada offered no canyons, only towering mountains and rocky passes of similar relief to that grand canyon hike.

The Rae Lakes basin is tightly confined. The valley is runs almost perfectly in a South to North direction. Snow from Mt. Rixfordin the steep cirque-like southern confines of the valley feeds the 3 Rae Lakes to the north. Water eventually winds its way to hit Woods Creek and eventually the South Fork of the Kings River.

Once we arrived at the lower (northern most) lake for breakfast, the trail skated South for us on the eastern edge of the lakes for only a mile before quickly turning Southwest to cross a small almost-island just north of the upper most lake. This is where the climbing began.

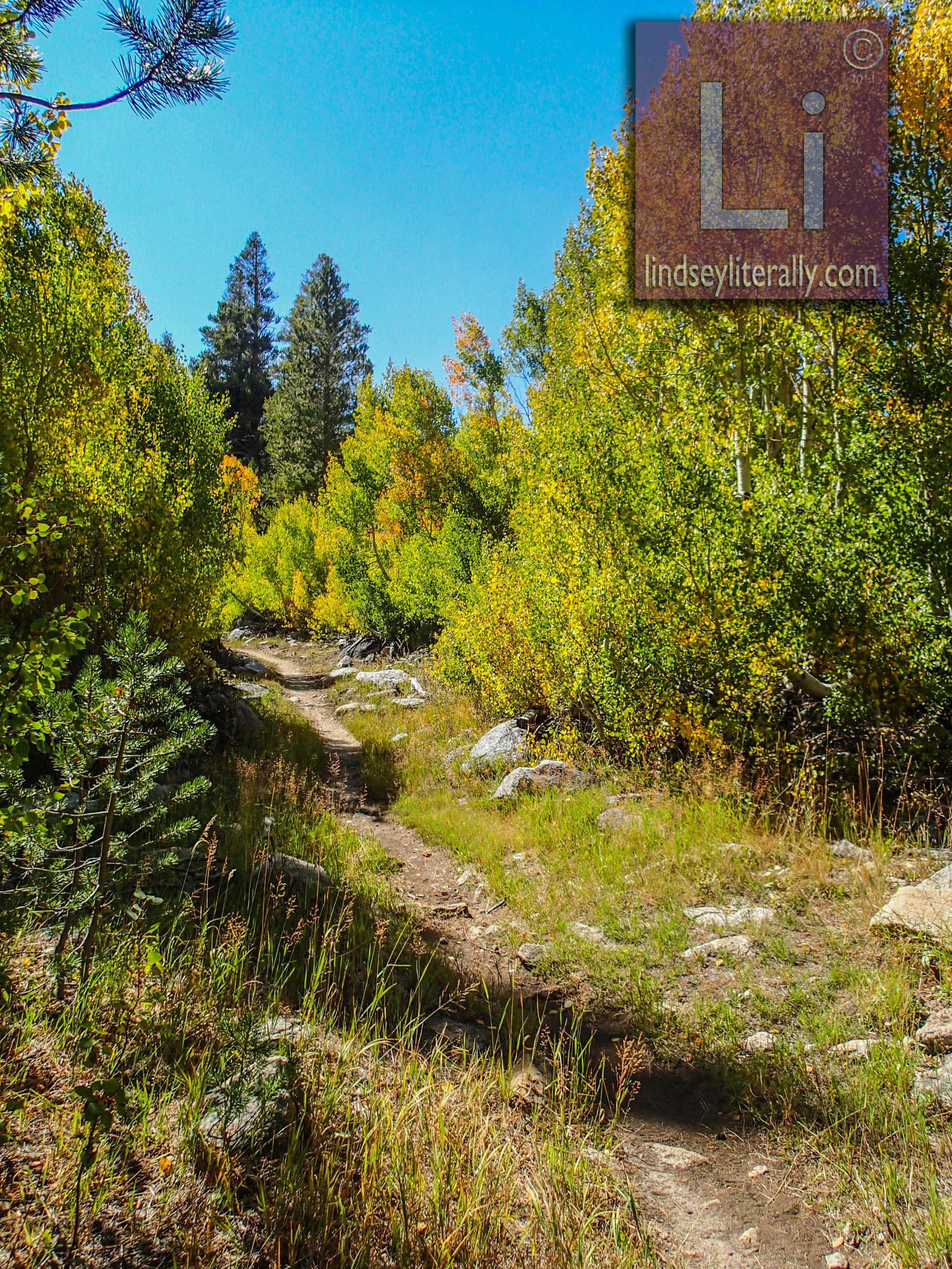

With relatively light packs (25 pounds or so) and a final destination in mind, the ascent started in a benign fashion. The trail climbs the igneous chunks of crumbled mountain to the South West of the first Rae Lake but the path is mostly in soft, green woody areas where vegetation has taken up residence. Intermittent shade, perfect temperatures, deep blue skies, deer grazing as they people watch made it the regular scene in the Sierra that was all too common- absurd perfection.

Less than a mile from leaving the first Rae Lake, the idyllic woodland walk gave in to a scene in the Sierra that was also all too common- the trees and shade cleared and before us was a bright grey mountain that was decaying. Boulders the size of school busses littered the land in front of us. The trail went up, but was visually lost very quickly in the cacophony of scree and mountain detritus towering in front of us.

Welcome to Glen Pass.

There is no real “base” to the mountain, but Lindsey and I stopped along the trail for some rest and electrolyte replenishment before the serious switchbacks started. It is a beautiful area. Like Muir Pass, there’s no way with words or photos to give any justice to the size and scale of earth that is out here. It’s a sobering reminder that even at the point in my life when I felt physically the strongest, I was powerless compared to the wars that created and were destroying this huge spire. You can almost feel the tension and power and anger and noise of the earth that existed over hundreds of thousands of years during this orogenic phase. I imagined the ground shaking, sky shattering, furious noise as this monster was born and subsequent intermittent bursts of screaming agony as billions of tons of rock and minerals broke off in unimaginably large chunks as the mountain slowly weathers back to the ground from whence it came.

The mountain was silent but the wind whirred like a jet turbine. Up ahead was the infrequent but unmistakable sound of rocks hitting other rocks. Humans massaging some of the mountain’s smaller offerings under their feet.

A map would tell you it was only 800 vertical feet from where we were stopped under the watchful eye of the Painted Lady to reach the top of Glen Pass. Those 800 feet of vertical elevation were the most gnarly, intimidating, and bad ass looking feet ever. It wasn’t daunting, or a cause for worry. Glen Pass is actually quite simple in the sense that it’s there. All of it. Right in front of you. You can see the top. You can see where you are. You can see the terrain you have to overcome to get there.

So it went, sucking in lungfuls of clean and bright sierra air and walking the well-built trail that was created between the boulders. Lindsey and I and a handful of others walked to the top of the pass that day. Nearly half way up the mountain near the end of some steep switchbacks we met a couple of women on their own adventure. We traded photographer duties, all four of us realizing that this was most certainly a “I can’t believe I did that” moment.

With my hiking stick in tow but not really doing much work, I plodded ahead. Lindsey and I would swap positions but 90% of the time she set the pace. Following the switchbacks the trail mercifully levels out a bit and gradually climbs a long gradient to the pass. When we arrived, Lindsey and I were the only ones up there. The world we’d come from that morning looked small.

The terrain on the other side of the pass looked just the wasteland as what we’d climbed. We couldn’t see where we’d end up. The shape of the valley didn’t afford that opportunity.

It was about mid-day by the time we crested. We didn’t linger long on the mountain pass. Lindsey wandered off behind some of the more modest sized black boulders to pee. I stood on the pass penultimate to the peak as I pondered our position.

“Just recall that at the end of today, you will be sleeping in a hotel and have hot food and access to a shower at the end of today” the part of my brain that doesn’t waiver and accepts the inevitable facts of time said.

The wind swirled around the pass like an invisible hand vigorously stirring a cauldron. It seemed to come and go in all directions with a purpose. Staring south and looking in to the vast, sharp terrain that lay ahead of us I replied to my prior thought aloud: “I don’t see how that’s going to happen…”

Lindsey popped back up from behind her black and white speckled diorite boulder.

“Ready?” I inquired

“Ready.”

Those words were carried away by the breeze and probably still lie stuck on some craggy scree slope of an unnamed mountain.

Via Domus

Outside of the Weimaraner brown rain-fly the stars woke up, mountains began their secret lives, and small insects came to life. The short and thin golden-brown crunchy grass that grew in the rocky loam enjoyed its respite from the sun and slowly turned an iota darker as it went about its cycle of life, death, and rebirth. The Sierra winds picked up and rocked the staunch, weathered trees back and forth. And the permanent residents of the Sierra Nevada looked towards the glowing nylon walls of our nightly home.

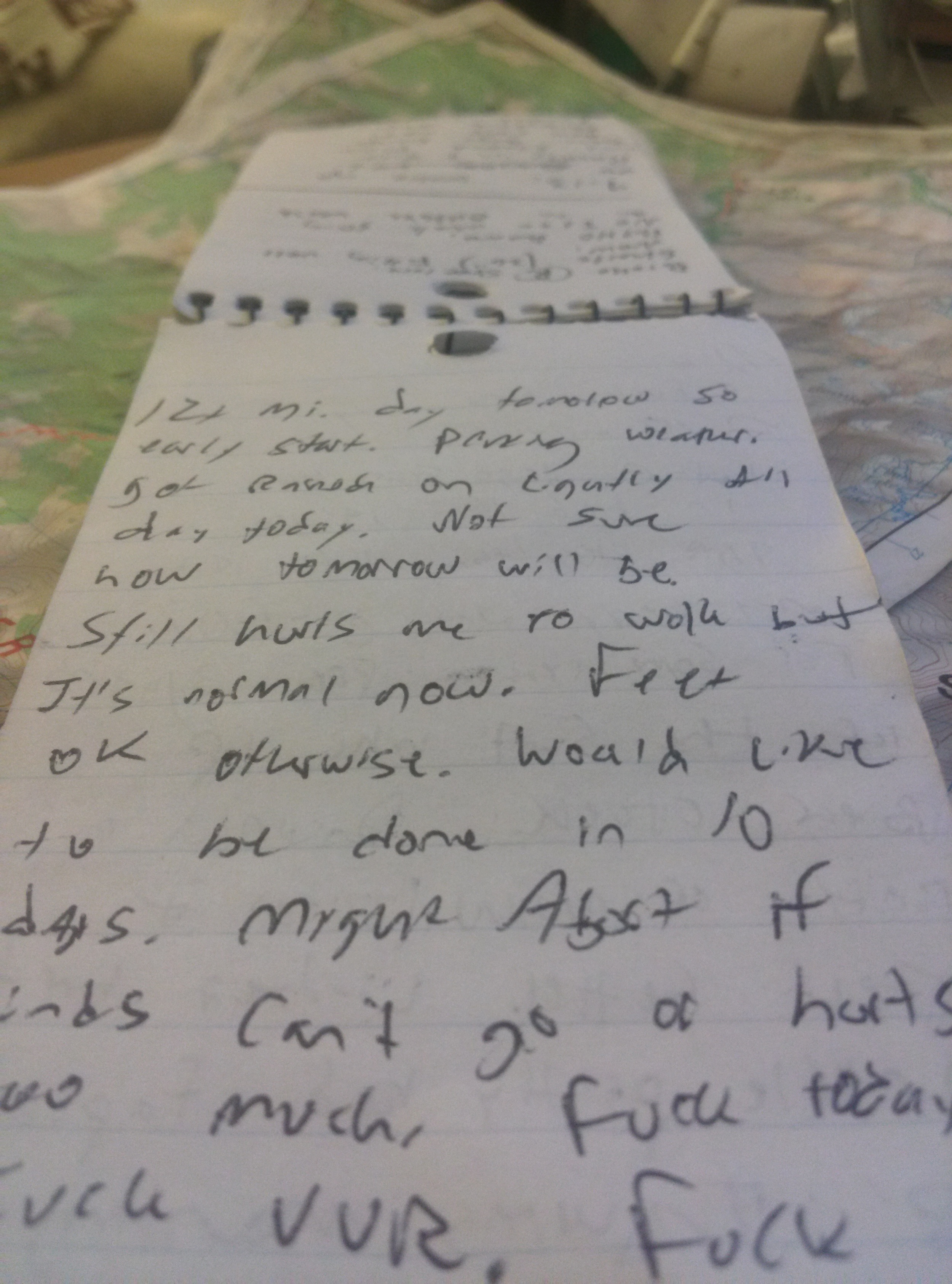

Plan.

It was not long after getting in to the tent that I began to feel better about the previous day’s hellish ending. Horizontality has very soothing, rejuvenate qualities to it. Maps were out, notebooks were open, pens were uncapped, and the trail guide book was sprawled open as Lindsey and I brooded over what was to come in the morning and the following days on the trail.

The good news, if there was any to be had, was that we had very little food which made our packs as light as they’d been on the entire trip. The bad news was that all of our artificially illuminated planning was for an exit and not a finish.

“Miles away” was my ultimate determination. We were miles and miles away from Onion Valley and we were a good few Passes from having our boots (or shoes, now) hit pavement. I studied the day that was to come featuring Pinchot Pass. Being appeased with our current elevation, its ultimate elevation, and the fact that it wasn’t named Mather, I put my personal effects in to the little mesh pocket by my head and curled in to my faithful and surprisingly not-too-foul smelling Marmot Arroyo sleeping bag.

The body shouldn't idly comply with what it’d been through the past 2 days; the reserve supply of food, the elevation gain and loss, and more specifically the muscle groups utilized and the required repetitive movement of them. I was certain I would awaken sore, tired, and absolutely on low fuel in every way you can imagine after the Golden Stair Case and Mather events.

The night was bright thanks to a full moon and the reflective granite mountains around us. Though the night was over quickly, life seems to move slower in the sierra. I’m inclined to think the sun does too, lazing its way above the horizon and hiding behind the cold gray granite before it inevitably shows itself and resumes its normal rate of passage in the sky. And why not? Why care about hurrying up or time at all for that matter? Seconds are days in the sierra. Minutes are months. All told, a year in the Sierra Nevada may as well be a blink of an eye. The mountains play by their own rules and have a pace all their own. The struggle is learning how the mountains do it and adjusting accordingly.

I woke with surprise that I was not stiff, aching and unable to move. I felt quite well by the time solar radiation began to reverberate in the thin and crisp dawn air. I prolonged my stay in my sleeping bag all the same, opting to maintain my horizontal state as long as possible. My fear was that Pinchot Pass would become another Bear Creek for me, and though every hike starts the same in the morning (a little slow, a few adjustments, a bit of time getting in to a rhythm) after about 30 minutes, the inevitable truth of the state of things comes out. Very soon after moving, you know what kind of day you’re in for.

The sun washed out the mountains and set the sky a deep indigo as we sprawled our belongings around camp. Slowly, things found their way in to their right place inside of our packs. My Osprey Exos 58 smelled like a homeless man save the tinges of stale urine. Hundreds of miles of carrying a bear vault had worn a hole in the hydration sleeve and back panel (and the bladder itself).

The bear canisters themselves echoed as we filled them with what little we had left.

Benefits of carrying a tripod for 150 miles.

Around 10am zippers closed, buckles clicked, and all at once we were standing on top of where we had slept. Everything we had was strapped on our back and the path home led south and east.

Lindsey started off a little slow. After my initial diagnosis of myself, I realized I was feeling great.

Hiking never got easier. There was still labored breathing, sore muscles, tired bones, rest stops, and sweat…so much sweat. We did get faster and better conditioned, though. From where we camped at about 10,800 feet, 3 miles and 1500 vertical feet kept us from Pinchot Pass. Pinchot Pass kept us from wherever we'd stop that night. That one night kept us from the end.

Part of me wanted to go fast and get there…to the very end. Part of me didn't.

The miles, the tendons, the lack of food hit morale hard. Yet still, I didn’t want to leave this landscape. I didn’t put too much thought in to it, honestly. I avoided thinking about it as much as possible knowing that if i did not avoid it, it would consume me.

Easy to do when your heart is thumping heavily as it forcefully displaces deoxygenated blood in favor of blood with the sierra air bonded to it.

We strolled past mountains as we ascended the lightly vegetated terrain. Below the peaks, glass-still lakes waited for the winter.

It’s quiet. Breezy but not windy. Brilliantly blue above us. Clouds nowhere to be seen. Not a sign of a soul in front of us or behind us. This area was ours alone. I prefer to think The Sierra Nevada was giving us a moment of silence. Truly, though, that's just life in the mountains.

The trail crested a saddle betwixt Mt Wayne and Crater Mountain. Beyond lay more lakes dotting a lightly vegetated granite landscape. In many ways, the view and descent were similar to the view and descent atop Mather. Everything about Pinchot seemed a bit smaller in scale though. The pass was a little easier, a bit lower. The view was immense but the valley below seemed a bit smaller, more hospitable.

Not long after 11:30am Lindsey and I started down towards the jagged peaks and cold ponds.

The landscape around Pinchot Pass is broken up by igneous intrusions, oxidized rocks, and rust colored scree piles that break up the color palate of the landscape.

Some wispy clouds would creep in as we sank in to the tree cover past Mr Cedric Wright, a fortress of rock that dominates the basin beyond Pinchot Pass. The trail follows Woods Creek in a south, south westerly manner passing a few small tributaries that feed the main creek. Lunch was taken just off trail at an unnamed water feature. Like all of the other sierra water masses, it was crystal clear, cold, and delicious to drink. The bottom was a very fine silt that was easily disturbed, but we couldn’t resist walking in it anyway.

Basking in the sun, we marveled at the landscape beyond the lake, ate our remaining rations, and enjoyed the respite from joint jarring, bone pounding hiking. I indulged in our last fruit roll-up.

It was the best fruit-roll up I’ve ever had in my life.

Not far beyond the lake, a side trail over Sawmill Pass takes off to the east. We’d talked about using this trail to exit the JMT but ruled it out speculating a lack of facilities and humanity (i.e. potential rides) at the trail head. The John Muir Trail descends in elevation beyond this junction as it follows the strengthening Woods Creek.

Shadows grew long as we left miles in our wake at the rate of about 3 for every hour. It was an emotional day. I can sparse remember the scenery that lay between the lake we stopped at and the famous suspension bridge over Woods Creek, and I can’t remember what the reason for the argument was, but I do know that for the 3 or 4 miles, we walked fast. Anger has a way of making the body move faster regardless of food supply, terrain, fatigue, squeaky tendons. So the silver lining of whatever useless argument we had which caused us both to be angry and walk far apart from one another was that we covered some ground.

Hiking south bound, the JMT makes its hard left across Woods Creek and in to a canyon. The sight of the iconic bridge changed the mood quickly, though it’d begun improving slightly earlier. This bridge was one of my first 2 memories when I was studying the JMT. I’d heard accounts of it, seen a photo, and gazed through my screen at a place I’d never be.

It’s larger than I thought. It’s higher above the creek than I thought. It shakes more than I thought. It’s like something out of Indiana Jones or Legends of the Hidden Temple. Quintessential rickety suspension bridge. It was realer than I ever thought it’d be.

Lindsey went across first after telling me to not shake the bridge while she was on it. Once she’d repeated that 4-5 times and felt slightly more assured that I might not shake it while she was on it, she walked across. I didn’t shake it, but only because I needed to video with 2 hands.

Once she was safely on the other side, I began my trip across as to oblige the aluminum sign on the pole- “One person at a time.” The bridge wobbled far beyond what I’d anticipated and I had to hang on to the suspension cables, but made it across easily. I would have stayed and played on it but some folks on a shorter backpacking trip were behind me, and I decided I didn’t want to look like a fool more than I needed to.

On the other side of the bridge, we watched shadows grow taller and we discussed our camping options for the night. We’d not gone as far as we needed to per my plan that I thought we needed to follow. On a giant trail side boulder I sat and ate a tortilla with Nutella on it and talked Lindsey in to hiking further. It was 4 miles to Dollar Lake from that point, and the hike was an ascent of about 2000 feet. It looked all very gradual on the map, though…

It almost always looks gradual on the map...

We hiked briskly as the sun started to fall behind the ridge in front of us. The streams and rocks and trees turned greyer as the world we were in fell in to the shadows.

It was a beautiful part of the trail, and another area I’d picked out as a good habitat for bears. I kept my eyes open but never saw anything. Spurred on by the idea of rest, food, and knowing that the end was in sight for this day and the whole trip, ultimately, we made it to Dollar Lake with time enough to set up in the waning moments of light.

Like the night before, as the sun went down the moon sprang up as if counter-weighted. It lit the sky in a side canyon beyond Fin Dome, and it was an hour before it surmounted the ridge and cast the area with bright white light.

The stars were incredible. I can’t fathom how it would look without a moon.

I stayed up and took some photos and watched the fish jump from the water to eat bugs and insects. Winds blew sporadically, at times making the surface of Dollar Lake as smooth as ice and other times making the whole surface smear with ripples.

With Diamond Peak high to our East, Mt. Clarence King in the West, and Fin Dome dominating the landscape South of us, we crawled in to the tent for what might have been the last time on the trip. We’d put ourselves in position to make it to a trailhead tomorrow with a 16 mile day. A 16 mile day that would have 2 passes…

The bear canisters lay far away from our tent, cavernous. Filled only with the first aid kit, a few snacks, fuel cubes. Tooth paste.

Not a soul else was around, and the mountain world was quiet. The moon and the mountains did their dance as we slept under the stars at Dollar Lake.

NOTES FROM THE TRAIL

9/18

21:14

14.7M, LEFT @ 10, HIKED TIL 1900

@ DOLLAR LAKE. TONS OF FISH. FULL MOON.

FINN DOME IN BACKGROUND

2ND TO LAST DAY.

TWO PASSES TOMORROW.

OUT TO ONION VALLEY

FELT GREAT TODAY W/ FOOD IN ME

SAD WE DIDN’T PACK ENOUGH TO FINISH

LEFT ACHILLES HURTS PRETTY GOOD.

CAN’T FEEL LEFT BIG TOE.

LOTS OF ELEVATION TODAY

10.5 ->12.1->8.9->10.5

TIRED.

I LIKE KINGS CANYON.

WARMER TONIGHT.

14.5 TO TRAIL HEAD.

Winter is coming

Day 14, 9.17.14

The darkness that draped us as we cooked the night before brought with it a certain chill, a cold that was exacerbated by being sweat-soaked. A change of clothes and a 30degree down bag did well to remedy the evening cold, but in the morning the temperatures had subsided even further creating a full on, bone freezing, blood slowing cold. At 10,600 and a handful of feet, the sun rises above the peaks late. Not a conducive combination to an early morning start.

As a general brightness slowly befell our tent that we’d parked under the foreboding gaze of Disappointment Peak, I made the most of my horizontal state. I wasn’t sleeping so much for rest, at this stage. It was entirely recovery. The longer I laid still and didn’t move, my brain figured that was all the longer for my muscles to recover from the constant incessant pounding of heavy footfall and other general abuse I put them through for 8 or more hours a day.

Lindsey was almost entirely ready to go, which I took as an indication that it was time for me to get up and get dressed and pack. I had made this process efficient enough by now; it would take me maybe 10 minutes to break down the entire camp, change, pack everything, have load-lifters adjusted to my liking and be trail-worthy. Others on this trip were not so expedient but they compensated by rising early.

Like many times prior on this endeavor, the lack of direct radiant heat is enough to keep you bed ridden. Life, for me, begins when direct radiation starts simultaneously killing and nourishing me.

Seems to be the trend, or at least a comfortable irony: that which saves you also tries to kill you. There’s an omnipotent but noticeably indifferent palpability to the world of peaks and valleys and trees and rivers of the Sierra Nevada. The sky looks on at you, knowing you’re there. It’s a presence you can feel. It does not care if you win, lose, conquer, fail, die, set a record, prove everyone wrong, prove people right. It’s just there. Cold clear air, pine trees with their rich scent of sap baking in the sun, cold infinite granite, bright intense light, flippant thunder storms, chaotic clouds.

It’s god damn beautiful. God. Damn. Beautiful. The Sierra Nevada deals out an experiential education for those who take the time to get to know it intimately enough. It renders life down to what it is at the core: a struggle. Our sad bastardization of life has given Struggle different faces for most people; sales numbers, quotas, laws, religions, wars, grades, salary. It’s all a struggle for life.

At no point is that more apparent than when bipedal feet compress the course grained sandy soil of the sierras while lungs struggle to oxygenate blood as your body climbs higher and higher over a timeless obstacle that was there before you, will be there after you, will not give a damn you were ever there, and will never tell a soul or star that you existed at any point.

Knowing the struggle of Mather Pass that we’d quickly come upon; today was a big day for me. In the morning, I laced up my Kayland Zephyr boots that I paid over $220 dollars for, the boots that hard carried me all of the miles so far. As I walked around with them and felt the pain in my Achilles, I decided it was time for a change. I got the pocket knife without thinking, because I knew if I thought, I’d talk myself out of it. I took off a boot and I stabbed it in the back as I began to cut off the top of the boot. Cold stainless steel cut through nylon, leather, foam, eVent with an unforgiving bite. When I was done and I put the newly modified Kayland Zephyr shoes on, it felt like sweet freedom. It felt like America.

It was near 9:00am when our liberated feet carried us forward on parts of the path we’d not yet traveled. With life packed in to 130 +/- liters of space between the both of us, we walked in to the unknown like we’d done every day prior on this trip.

Above us in the sky, clouds were absent and the atmosphere was a pale blue. Satellites and spacemen flew in circles somewhere far above us. Not so far above us, the blades of a helicopter broke absolute silence as it circled around, looking for someone somewhere around us. I had the feeling that the Search and Rescue team was trying to find us for as many times as we heard the heavy bass of the rotors thumping through the cold and thin mountain air.

Only a few hundred feet beyond our camp, we passed a few folks who’d also made this area home last night. In the light of day, the lay of the land revealed itself. It was an enticing visual treat, having set up under relative darkness.

It’s a beautiful area. The whole trail is, to be sure. But Palisade Lakes is a unique area of fleeting aesthetics. It’s much the same as all of the other lakes, but all at once really different. It sits ominously as a definitive marker before the infamous Mather Pass, of which I knew nothing about other than I’d heard it mentioned many times. Mather and Forester, Mather and Forester. Mather and Forester…and Whitney.

It’s a safe bet to assume that whatever pass you hear the most…that’ll be the hardest. People don’t repeatedly mention something because it was so easy. They talk about it because it was so hard, so taxing, so challenging and consuming that they can hardly believe they did it. Or in some cases, they don’t know how they did it. That which we obtain too easily, we esteem to lightly. No finer example of exertion and triumph than a mountain pass.

As we gently ascended the trail in a south easterly fashion, two meaty marmots scurried on the granite fragments that have fallen from the heights some time long ago to investigate the humans. By the time you hike to lower palisade (about 5 minutes after we left camp) you can see how the trail funnels you in to a mountain range, and there’s not a glaring low point or easy route. To get out, you have to climb. It’s nice at the least for the challenger to plainly show itself instead of hiding around notches or behind trees. Mather is bold in that way.

So on little food, cumulative fatigue, and conflicting thoughts about our food supply, one foot went in front of the other. And then the other foot in front of that one. Thousands and thousands of times. About 15 inches forward, about 5 inches up every step. That’s how we’d come over a hundred miles on foot, the hard way.

The trail switch backs up and forward through a vast boulder field. Some the size of buildings, some the size of footballs, but each one awkward and laborious underfoot. We came across a group of 4 or 5 or 6 people plodding ahead on the trail in front of us.

For the first time in my hiking life, I could tell I was better conditioned than someone else. Not in better shape, no. But reaping the benefits of acclimatization, and a body that expected to walk 10 hard miles every day.

Lindsey and I stopped to chat with them and it was in this dialogue when my fear was confirmed: Alabama beat A&M. One of the men in the group had a cousin or nephew who played for Oregon, and he said Alabama was still ranked #1. (Oregon was #2 at the time) All the same, it was the closure that I needed. With a heavy heart, we bid farewell and climbed upwards.

It was a bright day, a very very windy day. Cold, besides. I hiked in my usual Mountain Hardware Canyon shorts, Omni-Freeze shirt (I was freezing all on my own, but I liked the shirt too damn much) and I stopped to add my vest as we climbed ever higher. Up until this point, I’d not used the revel cloud vest except as a pillow or layering at night. Today I used it full throttle, reaping the benefits of synthetic insulation. Somewhere around 10,900 feet maybe, I put on my beanie. The wind was biting, and did too good a job of sucking away all the heat my body could generate. The layers were a life saver.

Like the Golden Staircase, (and every other climb) this was not easy. It does not matter who you are or what shape you’re in. You suck in air. You expel it. You repeat the process quickly. Your muscles crawl like an ancient tractor, and burn like a barn fire. You stop to recover often. As the summit came close, a rush of adrenaline fueled my empty aching muscles and spurred my pace up the mountain. After 50 feet, the fuel was gone and the summit was false. Dejectedly, I trudged upward slowly and steadily. Then- the summit. Adrenaline. Energy burst. 50 feet forward…exhausted. And no summit.

The third time that happened proved to be worth it as I crested a rocky ridge and looked down upon an expansive, beautiful land on the other side of the mountain. I yelled back to Lindsey that this really was the summit. Beyond the monster that we’d just surmounted, the grass wasn’t greener, and it was not the quintessential epic view that i’ve been conditioned to expect as someone rounds a blind corner or crests over a mountain.

Caged on all sides by mountains of different heights, the other side of Mather reveals itself as a valley both arid and lush off in the further reaches. The land immediately beyond was brown, dotted with lakes that danced from the howling wind. In the distance- more mountains that I assumed we’d climb over. It was part awe-inspiring, part heart-breaking. Two elemental feelings that up until then, and since, I’ve never felt at once. It’s a soul stirring compound in a good way.

Lindsey and I settled upon the serrated granite ridge and found a flat spot just off the trail. Betwixt boulders that served to block the persistent gales that continued to grow in strength, we kicked our feet up, ate Williams and Conner beef jerky and stared beyond our propped feet to speculate where we were going. Down, yes…but there was no telling where we’d be when the shadows got long, the trees turned grey and the mountains began to glow.

Blobs of molten turquoise broke up the brown landscape hundreds of feet below us. As our eyes traced the canyon past the arid landscape, some greenery began to line the deepest parts of the valley and even further, a full on lush forest of pine trees. At the furthest point we could see, a lake. This lake rested superior to the green valley below, and from Mather Pass, it looked to be 20 miles away and damn near at the base of another pass. It shone off far in the distance, the sun bouncing off it like a signal mirror as if it were looking to be rescued or at the least make itself known and say “here I am.”

The folks we’d passed who brought us the dreadful news joined us at the top of the ridge. 5 or 6 of them made their group. We swapped photographer duties, chatted, and we all rested at the apex of Mather Pass. For the 30 or so minutes we all shared that pinprick of planet where we were the entire world. Nothing else existed, mattered, or was real. Cold rock. Hard winds. Bright Sun. Soft flesh. Bloody muscle. Deafening vastness.

In truth I don’t think any of us stopped there so long to rest. It’s mostly basking, absorbing, taking everything in. The trail provides a lot of information to decode. At its heart, the simplest message that there ever was. It’s time. Billions of years of rock. Thousands of years of humans. Millions of years of animals. There are times when the enormity engulfs you like a rogue wave. This was one.

Each day is invariably a numerical statistic like it or not. How many miles? How many did you go, do you need to go, must you go? That lone omnipresent vise of time and subsequent required mileage is the only negative I can think of to thru-hiking. Having these brief moments atop mountains or lazing next to lakes or spending time under the trees are the necessary adhesives that make memories stick.

The winds whipped in a furious current from all directions as if it were an eagle and we were sitting in its nest next to its eggs. It felt angry that we were there. The hemispherical blue sky above was ambivalent. The desolate scrub land of brown dirt, sand, and boulders below us beckoned with a wiry smile any sane person would mistrust, daring us to come down.

Our friends descended first. The lot of them from California, they’d found time each year to section hike portions of the JMT. Our paths fatefully crossed on Mather Pass in 2013. Two kids from Texas with a crazy ass dream, a group of family and friends with a tradition. It wasn’t a spectacular meeting. It was good, to be sure. But how infinitely rare it is…Never again in that time and place will our paths and stories intersect; most likely never again will they. It’s always a privilege to share the time and space with people who choose to write their story on the pages of a wilderness path. They faded away like ants as they sank lower and lower in to the scrubby terrain.

Lindsey and I began the knee-agonizing descent about 15 minutes after they did. After a morning of screaming quads, calf muscles, and slow methodical plodding up a mountain, the gravity assisted downhill portion and incessant negative grade of the switchbacks made me miss the events of the AM but only briefly. I’m fortunate to have insanely strong knees and I much prefer hiking downhill than up. My hiking stick was still traveling faithfully with me, but it was nothing more than an instrument to pound out a cadence occasionally. Most often it just sat in my hand, idly by as sweat soaked in to the core of the wood.

On the maps, the arid scrub land is called “upper basin.” I renamed it to the tornado steppe for its barren, extraterrestrial landscape and the fact that it seemed to be the home of the angry wind god. The top of Mather was just an encounter with his angry winged disciple. Down here, I was blown off the trail more than once as the hard winds carried spoken words off in the opposite direction, angrily tore at hat brims and shirt tails, and roared like an invisible Vernal falls.

Traveling easily down grade, the JMT goes exactly where we’d speculated from our nest on Mather; down the canyon that births the South Fork of the Kings River, in to the sparse trees, and in to the forest. Here, the wind has less power, or it doesn’t care as much about you. Regular sound and silence of the Sierra creep back in instead of the chaotic cacophony of the Tornado Steppe. As we marched, we superseded the friends we’d met going up, on top of, and now below Mather. Though not hard compared to many other parts of the trail, this trek south seems long and with not many ideal water sources were available at this time of year until miles down the path.

It was hours before we were in proper tree canopy. The miniscule South Fork began its meager fight through soil, sand, igneous rock to get to an ocean somewhere. As we hiked along and it grew from streams and high mountain lakes like Cardinal, Lindsey and I stopped to get water and to obtain calories from our bear canisters. Next to the shallow, soft spoken stream we stopped. Sitting upon granite rocks surrounded by a sea of short, thick, crunchy yellow grass we ate a fruit roll up, pemmican bar, and examined the contents of our food cache.

Since leaving the horses, dogs, 5 gallon buckets, and only sign of civilization we’d seen in weeks at Muir Trail Ranch, a violent pendulum of stay-on-trail/go-home swung erratically.

Sitting there packing our resupply at the ranch, we were leaving. Exiting the trail that day and going home. The next day, we were staying on the trail…determined to make it. And then Lindsey found out I didn’t pack a lot of food. And we were going home. We climbed the Golden Stair case rationing what we had left, carefully analyzing and predicting what we would need and when, based on the difficulty of the days ahead; the hardest days of hiking on the JMT, period...and we could make it. We would stay on the trail. We went back and forth in our collective appraisal. At sometimes, we thought it’d be impossible to do it with the food we had. Other times, it’d be hard but we’d make it. Other times, we could ask other hikers for food. Or a ranger station. Or find some solution.

It was a goddamn torture rack of thought, hunger, and expectations. A bad chess game about to come to an end. We had a king and a pawn and we were running in circles on the board with the writing on the wall just to stay out of checkmate hoping for some kind of miracle or turn of fate as the opponent, Kings Canyon, sat comfortably unmoved from its place on its own board; smiling as its comrade pieces of wind and mountain and weather and miles sought to test us and take our energy and resources until we’d fold.

As we sat there surrounded by the brown grass battle ground that was already preparing for the winter that was coming, the pendulum flew off its wire and fell decisively. Our king laid down its arms, bent the knee, and we were going home. In that moment there next to the whispering, uncaring South Fork of the Kings River where the struggle was decided, the permanence of the decision set in. The battles and spars before with logistics, injuries, resupplies were not final. This was. It wasn’t about pain, pride, time, ability…we just simply didn’t have enough food to sustain the both of us safely. After 2 days of hiking on maybe 3500 calories between the both of us, it was becoming clear that climbing 3 more passes/mountains was not going to be possible.

I wasn’t sad or angry, not nearly like I was at MTR. I was glad to know what we were doing at least and excited at the prospect of a giant, unholy mass of unhealthy hamburger. There were logistics to work out like where we’d exit, how/if we’d get a ride…but the rudder was turned and the course was set for Owens Valley by way of some point North of Mt Whitney

The forest grew thicker and our elevation lessened as we entered in to the thick green patch of land that we had spied from on top of the dominating blade of granite that is Mather Pass. All at once I never thought I could walk that far in a day, yet I never knew it would take that long to cover that small-looking of a distance. Scale and perspective is a funny thing on top of mountains.

In millions of welcoming fingers of fragrant pine needle canopy, we came across our friends from Mather. They must have passed us during our long break by the river, and our somber, slothly pace never gained ground on them the rest of the day. They were setting up camp in a sandy, well frequented area where a now modest South Fork meanders through with it’s clear cold water. Lindsey and I stopped and consulted the topo map. Only about 3/4ths of a mile beyond where we stood, and 800 feet above us was a ranger station at Bench Lake that might have food…worth checking, worth staying out of checkmate. Otherwise we’d camp around one of the lakes up in this basin.

Before the climb out of the South Fork of the Kings river valley to Bench Lake commenced, we stopped in a boulder field under the pine trees and ate an absurd amount of pepperoni. “We” means mostly “me” in this case. It’s a seemingly perfect food, but at no point was I ever too fond of it. I ate it happily but it was always too greasy for my liking. The fuel was a requisite of climbing the final ascent of the day, I rationalized.

I’ll be damned if it did a single thing for me…climbing up those “800” feet felt harder than climbing the Golden Staircase. By the time we made it up the switch backs of the ridge and popped up on the lake basin where the ranger station was, I was fully and officially exhausted. We didn’t stop to find the ranger station, possibly because I was tired, grumpy, and didn’t care. We walked on ever upwards. Slowly. So slowly…like my legs were on life support churning out a step once every 2 seconds. Lindsey, having more energy, went ahead to scout a campsite while I mindlessly, aimlessly staggered on and off the trail. She found a suitable site and alerted me to its location. I used the final ounces of processed pepperoni energy to navigate to our home. I shed my pack with a “thump” and embraced the long shadows.

The sun counterbalanced the moon and as its yellow fire sank in the west behind Mt Ruskin. Marion Peak, and the other sentinels, the pure white light of the moon rose opposite over Mt Pinchot and Striped Mountain, casting a luminous white glow on us as the waning red rays of the sun fought to ignite the highest spires in the east as long as it could before succumbing to the horizon.

2 miles ahead of us on the trail: Pinchot pass. We were positioned to climb it in the morning. Only 800 feet ahead of us in the distance, as the light in the sky changed from white to yellow to orange to purple to black, the surface of a lake shone under the waning luminosity like a signal mirror as if it were looking to make itself known and say “here I am.”

NOTES FROM THE TRAIL

TUES 9/17 8PM

11M DAY.

CAMP @11,100 FT

COLD AS HELL.

MADE IT OVER MATHER @ 11:34, STARTED @ 8:50.

ROUGH DAY.

BIG CLIMB, LOW FOOD. CAN NOT FINISH.

EXITING @ KEARSARGE PASS, 31.3 MILES AWAY.

HEARD S&R COPTER THIS AM.

ONE FOOT IN FRONT OF ANOTHER GETS YOU FAR.

MOON ALMOST FULL. PAST 2 DAYS SKIES CLOUDLESS

WINDY AS HELL TODAY.

THINK I HEAR A COPTER AGAIN…

THIS IS NOT A TRAIL IT’S A MOUNTIAN CLIMB.

SAW 2 MARMOTS TODAY.

COLD AND WINDY ALL DAY.

READY TO LEAVE BUT WANT TO FINISH.

IN GOOD TRAIL SHAPE BUT PASSES ARE STILL STUPID HARD.

MATHER TOOK A LOT OUT.

ACCLIMATED, CONDITIONED, WEIGHT OPTIMIZED FOR LONG HIKES.

SHAME TO CALL IT OFF 20M SHORT.

CUT OFF SHOE TOPS TODAY. FELT BETTER.

TIRED IN GENERAL.

HUNGRY. COLD.

WINTER IS COMING.

FOUGHT THROUGH A LOT OF PAIN, HURT, AND UNKNOWNS.

HAPPY W/ HOW FFAR, HOW HARD, AND WHAT WE’VE DONE (160 +/- MI) SINCE OUR LONGEST BACKPACK BEFORE WAS 1 NIGHT

HOPE TO TAKE IT EASY ON WAY HOME.

READY TO SHOWER, EAT, FIX PHONE, SHAVE, MOVE, AND STAY IN GOOD SHAPE.

WILL MISS MTNS BUT BLOWING THROUGH THEM ISNT IDEAL.

MANY BEAUTIFUL SPOTS GO UNNOTICED DUE TO HEAD DOWN AND HEAVY BREATHING

LOVE THIS PLACE.

FREE. WILD, UNRUINED, ROUGH, VAST, HOSPITABLE, ANCIENT.

NOW TO FIGURE OUT EXIT LOGISTICS. HOPING FOR BIG (15M) DAY TOMORROW

Golden Rule

Day 13. 9.16.13

Beneath the boulders of the Black Giant we camped and we rested. The diffused light of dawn slowly filtered up the canyon and cast a cold light through the trees and creek. The direct orange rays bounced off the higher topographic lines of the mountains that flanked us and for a few minutes, the world glowed orange.

Inside of the North Face Mica 2, I ran my hand on the inside of the loosely staked out vestibule wall. Cold, but dry.

Today would be a good day.

Most of the days, it didn’t matter how far we would go or where we'd stop. The only exceptions were resupply days (which we'd finished by this point) and today. Back in Tuolumne Meadows as Riley, Lindsey, and I sat around a hydrocarbon fueled camp fire, Riley told us there were two distinct hikers he'd met as he walked North and the others walked south: Those who went up the Golden Staircase and Mather pass in one day, and those who planned their day to end after the Golden Staircase and then climb Mather the next. He noted that those who did both climbs (really more of one, long, continuous climb) in one day hated their lives. Accordingly, Lindsey had been eyeing mileages and planning on getting us to a spot where we'd not tackle both passes without a night's rest in between.

Lindsey's endeavors in bipedalism without pain were going well. Having no shoe tops had seemed to make all the difference. In my stubbornness and general unwillingness to cut up my $220 dollar boots, I pressed on in varying degrees of pain and varying amounts of tape and varying dosages of Aleve.

Our morning in camp was a quick one. Inside the cozy confines of the small tent pad that was sandwiched between pine trees and a granite boulder we went through the morning routine. It was not a super cold night or morning even as the sun struggled to rise above the heights of Mt. Gilbert, Johnson, Goode, and the others that made the mighty ridge to our East. Certainly, by this point in the trip, the routine was a finely tuned system; a well oiled machine of efficiency, repetition, function. The packing system was concrete. Even in the 58 liters of space, I knew where every item was. I knew what I needed. Best of all, everything in my pack, I used. There were no freeloaders, no luxury items that went unused. Every item had a purpose. It seemed almost like I didn’t have enough; I'd get bored at looking at the same 7 pairs of socks, 2 shirts, 2 shorts, and other few items. In reality, it's a feeling of exhilaration and a sign of precision. My life was in a backpack. I needed nothing, I wanted nothing. My food, shelter, love, adventure, health, and life was in, around, or tied to that bag.

Fully loaded and resting on the cold earthy soil, I yanked the pack on my shoulders with a quick, smooth motion that used to be hard when we started. I was getting stronger. I felt it. I felt my body changing throughout the trip, but this day was one of the first when everything came together as a whole.

The bright yellow sun baked the infinite Earth sky in to a deep blue. Cloudless skies; endless blue that would make Montana jealous. The trail would lead us East and South. We had camped on the upper fringes of tree line. We'd hike down in to Le Conte Canyon through an artery of the Kings River that bisected mountains. This Middle Fork of the Kings River synthesized from lakes, snowmelt, and high altitude creeks. The river did not exist before Muir Pass. As we walked the other side, the river was born. It's awesome watching something as simple and as oft overlooked.

A couple of guys speed past us. They're weekend visitors who've been in this area many times. The other creatures we see, a few deer, are foraging ahead of us. They keep their distance as they meander the path we're walking. Eventually they break from the trail and head down to water as the 2 mothers and 2 fawns eat shrubs.

Maybe 40 minutes in and somewhere around Big Pete Meadow we pull over to make breakfast. There are a good smattering of established campsites in the area and since the trail parallels the path of the infant Kings River, it's a great point for us to fill up, eat some oatmeal, and tend to any medical needs.

Aside from a little tape, blister prevention, and chapstick, I'm feeling good. The morning is an array of tangerine colored sun rays warming the granite ridges and prominent peaks that envelop us. As we hike overall Southbound, at this very specific spot on the trail there are monstrous, sheer spires to our right and a very steep high grade to our left. Water did this…kind of cool. A tall, lanky NPS Ranger stops by to chat. I figure it's a permit check. And it is, but he doesn’t make me break open the pack and get out the permit. Nice guy. We chat briefly and he carries on going North on the JMT. He's got the best job in the world. But he didn’t know the score of the A&M/Alabama game.

We march on with ease (trail is a comfortable grade and downhill during this part) past Le Conte Canyon Ranger Station. Here at the ranger station is a Junction with a side trail that goes out over Bishop Pass. 12.6 miles to a trailhead. Ever since Muir Trail Ranch, I wondered if we'd go out early and exit the trail on one of these access roads. I didn't want to, so my plan was to always just keep my mouth shut and hike on the JMT unless otherwise told.

The JMT is interesting in that once you're on it, you don't really want to leave the formal JMT. David wanted to hike the exact route, every step of the way. Lindsey and I didn’t care to that level of specificity, but we did care. I wanted to stay on the well worn ruts of the frequently traveled iconic Sierra trail. There's much to explore and there are hundreds of miles of side trail, obscure loops, little seen lakes, and all are worthy of visitation. But this was a John Muir Trail Trip. Plus Lindsey and I were both feeling pretty good, albeit a little dirty. The Bishop pass trail junction came and went.

Another 3.3 miles down the Middle fork of the Kings River (which had grown considerably since we first saw it at higher elevation in the morning) and the trail makes a hard turn almost exactly east. Before reaching this junction we pass Grouse Meadows. Beautiful spot.

We reach the trail Junction. JMT goes east, Road's End Trail goes south. We're surrounded by peaks. The Citadel to the northwest. Giraud Peak to the northeast. Rambaud Peak in the southwest and Mt. Shakespeare to the southeast. All of them roughly 12,000 feet and we're sitting river side, taking a hobo shower at 8,070 feet. We filter water, rest, refresh ourselves, and prepare for the impending ascent that is by most counts one of the most daunting of the entire trek: The Golden Staircase.

There are 13 maps in the JMT Map series that we had. We started on map 12. Today, we would start on map 5 and end on map 4. It was a good morale boost, not so much in an "ok-we're-almost-done-only-3-maps-to-go" way as a "damn. You've-hike-a-long-ass-way" way.